Welcome to the first edition of Strange Days, a newsletter in which i’m planning to talk a little about the movies i’ve been watching and the things i’ve been enjoying, whether that’s music, art, running, cooking, gaming; literally anything. I’m hoping this’ll be a monthly thing, though admittedly the only reason i’m here at all is because there’s a lot to talk about this time, so maybe it’ll end up being a one-off — at least until something interesting happens. Who knows! In any case, for as long as this lasts I truly hope you enjoy reading it.

October is an unusual month to begin this letter with. If anyone ever cared to take an average of the films I’ve watched over the past ten years or so, split by month, a decade of Octobers would almost certainly stand above the rest. October is a month of festivals, this year more than ever, and somehow I managed to watch a lot of films without seeing a single one at home. Thirteen films in London, fourteen in Vienna. Festival season always gives me a snapshot, but never more, of the most interesting new cinema I’ll see in any given year, and without getting into too much detail that was proven to be the case once again. Bonello, Hamaguchi, Haynes, Breillat, Miyazaki, Jude. It’s encouraging to know that even as the fabric of the world frays towards oblivion there are still filmmakers willing to embrace the messiness of modern life. I don’t remember a year in which I’ve been so consistently challenged by new cinema, and so rewardingly.

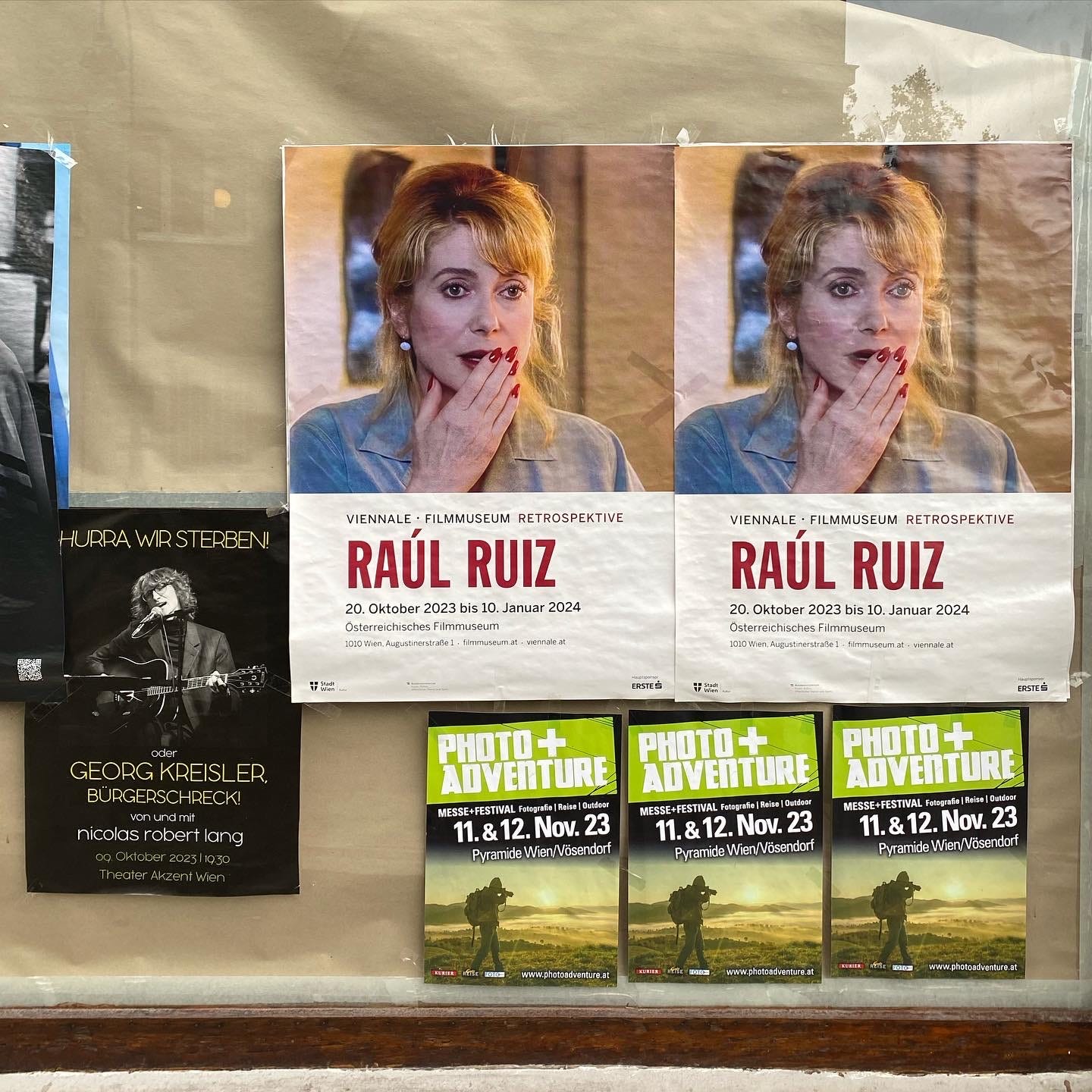

One side-effect of immersing oneself in the festival bubble is that new cinema tends to steamroll any opportunity to spend time looking backwards. That being said, I had a fun, if frustrating time seeing six Raul Ruiz films, five on 35mm, as part of the Viennale and the Austrian Film Museum’s extensive retrospective of his work. Frustrating, I think, because Ruiz is such a tough filmmaker to make sense of. He made more than a hundred films in his lifetime, across several languages, genres, forms, and individually these films are often dazzling and disorientating by design. Aside from the simple pleasures of the work, which, of course, is enough, I’m not sure there’s much to gain from a retrospective like this in the sense of fully understanding an artist like Ruiz. His work is too dense, too varied, too freewheeling to be neatly contextualised. I certainly didn’t find much to connect the six of his films that I saw, ranging from 1994 to 2008, but then maybe that’s my mistake for trying to find something in the first place.

In the end, of the six that I saw, and as much fun as I had, only La Recta Provincia (2007), struck me as a major discovery. The film, one of Ruiz’s final works and edited down from a four-part TV series, follows two people, an elderly woman and her son, who find a mysterious human bone carved into the shape of a flute near their home and feel compelled to embark upon a long and meandering journey across the Chilean countryside to find the rest of the skeleton and give it a Christian burial. On their search, they’re told an endless and ever-complicating stream of stories by the many people they encounter on the road: myths and folk tales, lies and tricks, histories and fantasies; and the purpose of their journey becomes hazier and hazier. Stories within stories within dreams within stories. I’ve never seen anything quite like it.

Away from the cinema, the highlight of October was a brief visit between Ruiz films to the Albertina Modern, a gallery just over the road from the Brahms monument in the Resselpark and around the corner from the Vienna State Opera, to see Yoshitomo Nara: All My Little Words, an exhibition spanning around forty years of the artist’s life. Nara’s work here is primarily comprised of cartoonish, childlike figures that seem too angry or violent or political or world-weary for their age, drawn onto a variety of materials: canvas, of course, but also envelopes, cardboard boxes, scraps of paper; sculptures too. The larger works tend not to have much background, if any, as if leaving these isolated figures exposed to anything and everything, and the smaller sketches exist within the boundaries of a previous life, recycled and transformed and salvaged having served their designed purpose. An enormous canvas of a child crying on a foldaway bed; a small pencil-sketch of a young girl wearing boxing gloves with the subtitle “NEVER ENDING FIGHT!”; a boy with a peace sign jacket and heavy boots carrying a knife and grinning maliciously. An exhibition of angry children with adult problems. A never ending fight.

Speak soon,

Matt